Editor's note: A version of this article ran in the January issue of BRAIN.

By Alan Cote

Wearable technology is nothing new to cycling apparel – from heart rate and fitness trackers to jackets illuminated by LEDs. But lurking in R&D departments of bicycle component manufacturers is something altogether different: designs that meld clothing with shifters. Namely: gloves and other handwear that include wireless controls for operating electronic derailleur systems.

Way back in 2007, Pearl Izumi launched a cycling short with an integrated MP3 player, with controls on the thigh.

But wireless technology allows a more modern approach. SRAM was the first to offer wireless shifting, with its introduction of eTap in 2015. Patent filings show that both Shimano and Campagnolo are also working on wireless shifting.

In January 2013, when SRAM was presumably deep in the development of eTap, they filed patent application 13/750,648, “Control Device for Bicycle and Methods,” with Kevin Wesling as the sole inventor. Wesling is currently SRAM’s global director of advanced development.

In January 2013, when SRAM was presumably deep in the development of eTap, they filed patent application 13/750,648, “Control Device for Bicycle and Methods,” with Kevin Wesling as the sole inventor. Wesling is currently SRAM’s global director of advanced development.

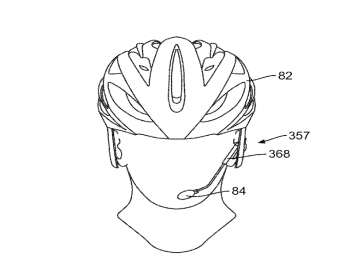

The application shows a wearable control device that communicates wirelessly to bicycle components, derailleurs in particular. Several versions are shown, with the one described in the greatest detail being incorporated into a glove. A helmet-mounted version that accepts voice inputs via a microphone is another embodiment, though described in less detail.

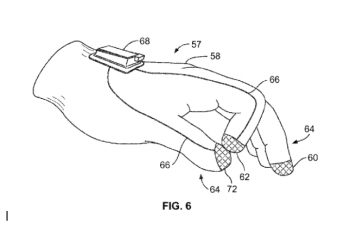

The glove uses several tactile buttons at the fingertips, wired to a processor, transmitter, and battery, shown on the back of the glove. Button types can be pressure-sensitive switches like mechanical and piezo types, operated by pressing a fingertip against a hard surface. Also shown are conductive-type sensors that work by touching two fingertips together. Other sensors envisioned use acceleration or change-of-position to initiate a shift. These are built into right and left gloves, for controlling front and rear derailleurs respectively, or both derailleurs can be controlled by buttons on a single hand. The electronics may be removable to allow washing the glove.

Meanwhile, Campagnolo presented a competing system, in a 2019 filing, US 16/419,675 Bicycle Control Device (an Italian patent application was filed a year earlier). Christian Marangon and Fabiano Fossato are the inventors.

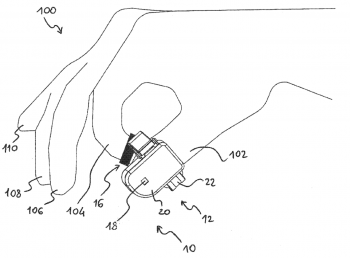

The clear difference compared to the SRAM patent, which Campagnolo cites, is that the design is a one-piece unit. Switches, transmitter, and all other electronics are contained in a pod that straps to a finger/thumb. The pod may optionally include a cyclometer-style display to show riding metrics like speed, distance, or gear ratio numbers.

The Campy design eliminates wires-down-the-back-of-the-glove in the SRAM configuration. But of course, this requires the pod to be attached to a finger or thumb – care would be needed when reaching into your back pocket for a snack, for instance. If the package could be miniaturized enough, it could remain unobtrusive.

Campy describes a wide selection of proximity and contact sensor types to signal a shift, including magnetic types.

No samples of either of these wearable shift switches have been seen. SRAM filed its patent application about eight years ago, suggesting they may not have a strong interest in commercializing the design. SRAM declined to comment on this patent application, as is common practice.

Campagnolo’s patent applications are less than two years old, but the company has yet to release wireless electronic shifting – if and when they do, perhaps a finger pod will be an option. Campagnolo also declined to comment.

Wireless shifting, in theory, opens up the possibility of third parties breaking into shifter sales by offering wearables (or bar-mounted pods) that can communicate with the major brands’ electronic derailleurs. A small electronic gadget likely presents a lower barrier to entry than producing an entire compatible brake/shift lever – though proprietary wireless protocols like SRAM’s Airea certainly present obstacles. There could be an easier path should Campy or Shimano use an existing technology like ANT or Bluetooth.

Monkeying with electronic shifting is nothing new: Fairwheel Bikes of Tuscon, Arizona, hacked into Shimano’s Di2 in 2010, shortly after Shimano released the system. Meanwhile, prior art cited in SRAM’s proceedings shows earlier wearables, like US Patent application 13/520900, “Hand Wearable Control Apparatus” – a single-fingered glove with integrated buttons for controlling GPS and similar functions.

Are Campagnolo or SRAM using their patent applications as part of an intellectual property strategy to block others from entering the wireless shifter space, with little intention of actually producing the wearable items? Or are finger-clicking shifters on the horizon? Only time will tell.

Alan Coté is a Registered Patent Agent & principal of Green Mountain Innovations LLC. He’s a past contributing writer to Bicycling, Outside, and other magazines, and a former elite-level racer. He also serves as an expert witness in bicycle-related legal cases.