As late as December of 2023, any number of industry pundits had publicly forecasted that the sales/supply situation will have normalized itself by now, which is to say, the third quarter of 2024. By then, they said, the cycling industry would be back to more or less what it was like in 2014–2019.

For the record, I was not one of them.

Instead, we find ourselves in a bizarre market reality where retail sales are spotty and many — but by no means all — customers remain shy of purchasing. We are plagued by both under- and over-supply of bikes to sell, depending on model type and price point. Round after round of industry layoffs continue with no sign of letup.

On the national front, a jittery stock market is stoking long-held fears of pending recession and a further decline in consumer confidence. On the other hand, at least some customers are starting to come into retail businesses and actually making purchases. (The linked AP article features a nice picture of a consumer shopping at University Bicycles in Boulder.) And according to both PeopleForBikes and the National Sporting Goods Association, ridership is holding steady at COVID-era levels, and is higher than it's been since 2005. So the news is not so much doom and gloom, but more of a mixed bag.

The big picture

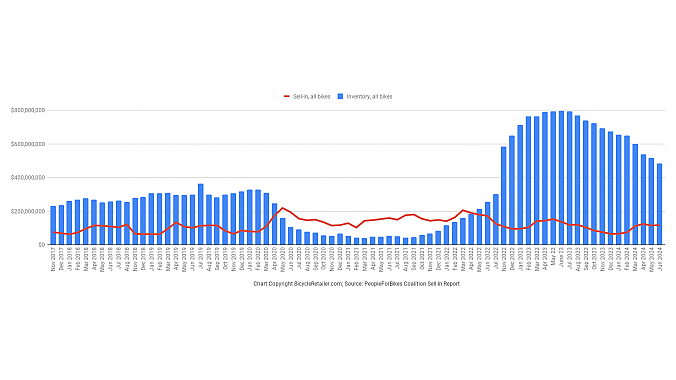

The industry is struggling with two problems: too many inventory dollars at suppliers (combined with shortages of the models that are in demand with retailers), and not enough customers for those overstocked bikes at retail. Here's a chart BRAIN made from PeopleForBikes data showing supplier inventory vs. sell-in to retailers from November of 2017 through June of this year:

You can see the historically normal inventory levels 2018–2019, the drop-off in response to demand during the COVID years, and the build-up of record levels of inventory beginning in late 2022, reaching its peak in summer of 2023. You can also see that those levels are starting to come down, although they're still very high compared to historic norms.

With the exception of the pandemic years, sell-in to dealers has remained fairly constant. But in 2018, the ratio of inventory dollars to sell-in was 2.9:1. As of June 2024, it was 4.1:1. (Thanks to BRAIN Editor-in-Chief Stephen Frothingham for these stats.)

I reached out via email to PeopleForBikes senior research manager Liam Donoghue to help clarify what's going on. Here's what he had to say about current conditions:

"May 2024 sell-in [dollars] was 8% higher than the May average over the four years pre-COVID (2016–2019), but was 35% lower than the four years since the pandemic (2020–2023). It's tracking pretty darn close to 2019 and the first three months, at least, of 2020."

In terms of supplier inventory, Donoghue said, units in May 2024 track within 1% of 2017 and 2019 levels, but the dollar inventory (which is what the chart shows) is 74%–131% higher. "So a very similar level of total bikes are in supplier inventory compared to pre-pandemic, but they're simply skewed much more expensive now." And, as the chart further shows, those excess inventory dollars are coming down, just not as fast as we might prefer.

Moreover, he said, "Bicycle sales at retail are telling a similar story in that total dollar volume in May 2024 is within +/- 6% of 2016–2019 numbers, but unit volume is down 29–36% for the same pre-COVID years." Which translates to: Dealer sales dollars to consumers are comparable with historic norms, they're just not selling as many units. And, dealers tell me, bike sales — whether in units or dollars — vary widely from market to market and even from store to store.

The dealer's view

Current dealer margins are so low that the upside of selling a few more units pales beside the risk of holding onto inventory that doesn't turn.

Part of the reason supplier inventory dollars are still so high is that retailers are declining to put large numbers of bikes onto the sales floor if they're not certain those units will turn in a reasonable amount of time, regardless of what extended terms or discounts are offered. And of course what amount of time is "reasonable" varies from dealer to dealer.

I've mentioned this in past pieces, but here's a more detailed view of the phenomenon: By keeping their own inventories lean in uncertain market conditions, dealers are passing the inventory risk back up the supply chain to suppliers. Now compare and contrast this scenario with the pre-COVID Bike 3.0 model, where suppliers loaded retailers up with six month's worth of inventory at a time, subsidized by long credit terms. And with it, 100% of the accompanying inventory risk.

Some dealers even tell me they'd rather risk losing a sale to a brand's consumer-direct or Click & Collect channels than assume the inventory risk of carrying bikes they may not be able to sell in today's consumer climate. Current dealer margins are so low, they say, that the upside of selling a few more units pales beside the risk of holding onto inventory that doesn't turn. If nothing else, they can make up the loss of a direct sale with aftermarket service revenue from the customer.

Brands are playing the same game from the other end, by holding onto internal inventories of popular models to ensure they will be able to support their own D2C and/or C&C efforts. If the dealer doesn't stock a particular model or size or color, the consumer can always buy it from the brand's website.

Is this transfer of inventory risk a temporary thing, or will it become a fundamental part of the Bike 4.0 era? Only time will tell. But my bet is that as the inventory crisis subsides (maybe a year from now, maybe even later), consumers return to bike shops, and dealers become more comfortable with taking risks on inventory, so will brands' ability to pre-sell large amounts of product preseason.

We may yet see a return to the timeworn "if you don't order a bunch now you won't be able to get any later" argument. Just not anytime soon.