Adapted with permission of VeloPress from "Bike Mechanic: Tales from the Road and the Workshop" by Guy Andrews and Rohan Dubash with photography by Taz Darling. Preview the book at www.velopress.com/wrench.

MUCH LIKE YOUR LOCAL BIKE SHOP, JUST WITH MORE STOCK

Every professional cycling team needs a headquarters — a place where it stores everything needed to keep 30 riders on the road. At the service course there's everything you can imagine you'd need, from spare team-bus toilets to bed mattresses and bottles of water to physical therapy supplies. There are shelves full of jam, detergent, and chamois cream. Toothpaste, beer, and bleach. It's a bit like a bike shop mixed up with a supermarket, without any registers.

And that's not even mentioning the tools, the spare parts, and the bikes.

Riders usually have four team-issue bikes. They keep one at home, and three — including a time trial machine — stay at the service course. Some riders will have more. Time trial specialists, for instance, will usually have two TT bikes. There are usually cyclocross bikes and mountain bikes kicking about, too, for winter training and off-season racing. Of course the Grand Tour G.C. riders may have a yellow and a pink version of their racing bike, perhaps.

These days riders do not have to travel with their machines to races. The bus will deliver their bikes prepped and ready to roll. Most teams will also bring along fresh kit, helmets, even shoes, so all the riders have to do is remember to take their toothbrush. Spoiled they are, spoiled.

Since the service course is where all the storage and bike building happens, most of the mechanics will live near it. That's even the case if they hail from Australia and the service course is based in Oudenaarde in West Flanders. As Bob Farley, veteran Aussie team mechanic, says, "You have to be near the material." "Material" is mechanic speak for bikes and components, so during the racing season Bob moves to Belgium, heading back at the end of the season for well-earned rest and, he hopes, some sunshine.

Since the service course is where all the storage and bike building happens, most of the mechanics will live near it. That's even the case if they hail from Australia and the service course is based in Oudenaarde in West Flanders. As Bob Farley, veteran Aussie team mechanic, says, "You have to be near the material." "Material" is mechanic speak for bikes and components, so during the racing season Bob moves to Belgium, heading back at the end of the season for well-earned rest and, he hopes, some sunshine.

With so much of the team personnel based nearby, the service course becomes a social center for those involved with the team. Riders drop in after training rides for coffee and a chat; it's got a warm friendly feeling to it, just like your local bike shop.

Since the service course is a relatively functional space, it is often housed in an out-of- town industrial park. The precise locations are often closely guarded secrets, and there is unlikely to be any branding on the outside of the building. With the amount and value of equipment required to run a team, security is a big issue these days — World Tour teams have been followed back to the service course to be robbed. An out-of-town location is also sensible because it tends to offer convenient highway access for big trucks and the team bus.

There is a general location for service courses, however: Belgium. This is even the case for UK-based teams. Team Sky has a satellite service course in Belgium. There are several reasons. First off is that the Spring Classics mean the first half of the racing season is almost exclusively in or near Belgium. Then there's the fact that many of the bike manufacturers and component suppliers have their European headquarters in either Belgium or Holland. Finally, teams historically recruit Belgian mechanics, soigneurs, directors, and team logistics crew. Cycling is Belgium, as the saying goes.

So to see a team preparing for the new season, we naturally headed there.

PROFESSIONAL BIKE TEAMS NEED EQUIPMENT AND LOTS OF IT

Omega Pharma–Quick-Step’s service course is near Wevelgem in West Flanders, Belgium. It is a lot more like a team head office than an old-school service course. Alongside the workshops and storage areas are offices, meeting rooms, and a small museum with a collection of team boss Patrick Lefevere’s favorite former team bikes. It’s home to Johan Museeuw’s Eddy Merckx from his final Paris–Roubaix victory in 2002. The bike still has a piece of tape on the stem with the pavé sectors marked and is caked in good old mud from the Nord Pas de Calais region, just a few kilometers away from the Belgian-French border.

Dominique Landuyt has been a professional bike mechanic with Belgian teams since 1991. When we visit the Omega Pharma– Quick-Step service course at the start of the 2013 season, he’s been building up the Specialized Tarmac SL4 and Roubaix team bikes for nearly two weeks. The mechanics have to assemble them from scratch: each bike is built from individual components from the frame up; they don’t just grab a box from the manufacturer and spin a pair of pedals onto them. Each bike is time-consuming because every rider has special requirements, everything from the handlebars and stem to the position of the brake controls. The preference in thickness of handlebar tape and strength of pedal spring release is all noted. There is a huge spreadsheet with all the information on it, from crank lengths to saddle choices — no two riders are exactly the same. Tall or short riders pose a whole host of fit issues, and when the team is only using stock frames there can be a fair amount of headscratching involved in working out how to get the rider to fit the bike.

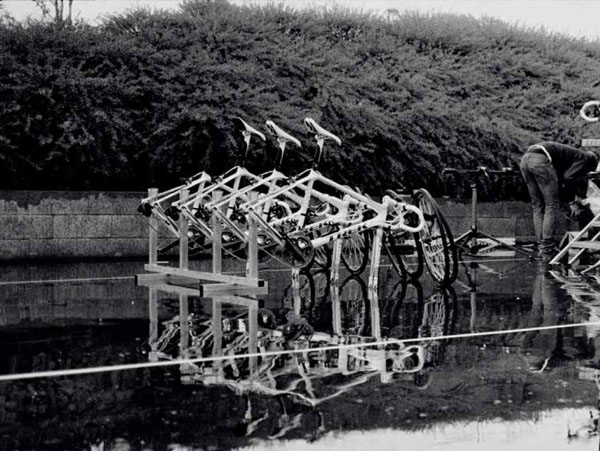

Dominique lives nearby and quite likes this time of year — he gets to do a “proper job” and isn’t out on the road for weeks on end. “The best thing about this job is that you see lots of different countries; the worst is when your kids are sick, and you can’t be with them,” he says. He talks as he works, and it’s clear he has huge enthusiasm for the sport that he grew up with. “My father had a little pro cycling team; he was directeur sportif for many years, and through the years there have been a lot of riders and characters, but I’ve survived them all. I’ve seen a lot of hard races, too. The best is always Paris–Roubaix, but it can also be the worst day to be a mechanic — like in 1994, the year Andrei Tchmil won Paris–Roubaix, the weather was like a horror movie and the mud was stuck to the bikes like cement.”

Dominique lives nearby and quite likes this time of year — he gets to do a “proper job” and isn’t out on the road for weeks on end. “The best thing about this job is that you see lots of different countries; the worst is when your kids are sick, and you can’t be with them,” he says. He talks as he works, and it’s clear he has huge enthusiasm for the sport that he grew up with. “My father had a little pro cycling team; he was directeur sportif for many years, and through the years there have been a lot of riders and characters, but I’ve survived them all. I’ve seen a lot of hard races, too. The best is always Paris–Roubaix, but it can also be the worst day to be a mechanic — like in 1994, the year Andrei Tchmil won Paris–Roubaix, the weather was like a horror movie and the mud was stuck to the bikes like cement.”

To be a good mechanic you have to be a lot more than just a hard worker; you need to be constantly ahead of the game and know what innovations are coming. And you need to be resourceful. Good teams use good mechanics, and good mechanics will keep good components going for as long as they can. Chains and cassettes will be replaced in accordance with the recommended life expectancy. That means chains will generally be replaced after 2,000–3,000 racing kilometers, depending on the weather and the type of rider (some wear out components quicker than others). Most teams will build around 150 bikes at the start of each season. As Garmin mechanic Kris Withington told me in 2009, they have to be careful how they use spare parts — they can’t just hand them out. “The first year that we did the Tour, we changed the chains on both rest days. Last year we used two chains, put a new chain on at the start and another halfway. But generally we use the material until it’s finished.” Even so, pro teams are supplied a large amount of spares by their suppliers.

But before we go any further with team support, we need some historical context. Back in 1973 things were slightly different. The service course was usually the back room of a bike shop. It was the year Shimano launched its first pro-level Dura-Ace group, at a time when Campagnolo dominated pro-team component supply. For many reasons this was a brave step for the Japanese firm.

Shozaburo Shimano and Tullio Campagnolo both rose from impoverished backgrounds to oversee powerful bicycle companies, and both shared a love of engineering and bikes. They shook hands when they met; perhaps through all their hard work they had earned each other’s respect. Yet their meeting took place when the two companies were on a collision course following Shimano’s move into bicycle racing.

Campagnolo couldn’t have been very worried at first. Why would it be? As a brand, it was race-proven — a massive technical advantage over Shimano — but more importantly it had massive clout. In the closed world of European racing, Tullio Campagnolo was a powerful man. The more romantic cycling fans criticize Shimano’s lack of history and absence of a racing legacy, pointing to the paucity of team support and success in major road races until Andy Hampsten’s 1988 Giro d’Italia win began to loosen the Italian stranglehold. But in 1973, whether it was aware of it or not, Shimano was facing a fiercely guarded monopoly. The only way it knew how to do it was to sponsor a squad — at huge cost, no doubt. And so along with the component groups that went to Europe was a team of product engineers. Then, as now, Shimano was there to learn.

“I liked him. He would always be at the races. We assembled all De Rosa bikes with Campagnolo parts of course, so I knew about their components inside out. One day I suggested to them to modify the front derailleur cage shape by one millimeter so the chain shifts properly and doesn’t drop. The Campagnolo mechanic looked at my suggestion and gave me a thumbs up. Two weeks later, it was out as a production model. Amazing. I always gave them my feedback, because they would use it. In return, Campagnolo gave me everything I needed at the races.” — YOSHIAKI NAGASAWA ON TULLIO CAMPAGNOLO

Its first team, the traditional and fairly conservative Belgian outfit Flandria, could not have been a fussier team to sponsor. Its leaders were Walter Godefroot, the experienced Belgian champion, and rising star Freddy Maertens, the young, brash, and hugely talented sprinter who could challenge Eddy Merckx in a sprint.

Being from the heartland of Belgian cycling, the team expected to win. Impressed by the surprisingly well-finished Dura-Ace components, Flandria’s influential equipment managers signed Shimano to kit out their bikes, helping change the consensus view that the Japanese firm was destined for the utility market. Among the new developments, Shimano added a spring into the pivot bolt of the rear derailleur, allowing it to swing around its fixing point. This meant the derailleur could cope with larger variations in sprocket size, eventually leading to the servopantagraph system, which became the derailleur norm.

Back in the 1970s, racing bikes used closer ratios, and the gears were smaller jumps. That meant the Campagnolo single-pivot spring system coped far better with the demands of the racing bicycle and environmental conditions; there was, quite simply, less to go wrong. As former Flandria team mechanic Freddy Heydens remembered, “We did have some problems. Those first Dura-Ace components were difficult to install and adjust, and the chains kept coming off. It seemed riders never stopped complaining about the group.”

Shimano was quietly ambitious and keen to learn more about road racing, so instead of making a PR fanfare to announce its arrival in Europe, the firm choose to simply distribute a few groups and drop a small band of mechanics and engineers in at the deep end. The feedback took time. Shimano insisted on written reports from its representatives after every month of racing. One of the correspondents sending information back to the Sakai HQ was mechanic Hiroshi Nakamura, and he was clearly realistic about the components’ limitations. “My first impression of a European road race was one of complete mayhem,” Nakamura remembers. “It was not uncommon for components, Campagnolo and Shimano, to break, and I remember the beating that our Crane derailleurs took at Paris–Roubaix. . . .”

“The relationship between the bike manufacturer and the sponsor is very important; it’s like a family. You need this relationship for the best results. The sponsor puts in the money, we supply the bicycles, and the riders put in the heart. You need to work together.”— ERNESTO COLNAGO ON TEAM SPONSORSHIP

In the 1973 pro peloton, one team rode Shimano, three Simplex or Huret, and nine Campagnolo. By the time Shimano took part in its first Grand Tour, the odds had evened up a little. As former marketing and PR man Harald Troost explains, Shimano was always determined. “They’ll do anything, anything that can help them to get an understanding of racing conditions and racers’ needs. It’s really hard to imagine, but the engineers come to the races in Europe and ask questions, they watch and learn, then they go back to Japan and a year later they come up with something that blows you away.”

Nothing changes much at Shimano. The guys who got the ball rolling in the ’70s are still there, and many of the senior staff have been at the company for most of their working lives, employed as development engineers, then managers, then directors. Masahiko Jimbo was once on the circuit in Europe, testing prototypes and developing ideas with the professional mechanics and riders. Today, after more than 30 years’ service, he is director of marketing. Hiroshi Nakamura is now director of Shimano’s bicycle museum. Such lifelong allegiance to a company is, of course, standard practice in Japan. But this is also what makes Team Shimano a fascinating and highly effective machine. For example, a handful of guys controls its entire worldwide marketing. Several bike companies have 20 or more marketing executives, and here is Shimano, the biggest bike company in the world, with a marketing team that would fill a phone booth. As Harald Troost explains, this is just how they do things. “The product always comes first. The idea is that when we make the product really outstanding, both in technical performance and in design, huge marketing efforts are no longer needed. The quality of the products is the best PR tool that we have.”

Today Shimano is perhaps the biggest professional team supplier. Currently it supports seven teams on the World Tour circuit, so going on standard bike supply levels that’s about 1,000 groups, which is around $4.1 million’s worth. Then there are the wheels. Shimano also sponsors around 100 individual athletes for shoes and makes bars and stems via its Pro range. Team sponsorship alone is a huge part of its global business and a large proportion of its marketing budget.

Today Shimano is perhaps the biggest professional team supplier. Currently it supports seven teams on the World Tour circuit, so going on standard bike supply levels that’s about 1,000 groups, which is around $4.1 million’s worth. Then there are the wheels. Shimano also sponsors around 100 individual athletes for shoes and makes bars and stems via its Pro range. Team sponsorship alone is a huge part of its global business and a large proportion of its marketing budget.

Campagnolo, meanwhile, remains the longest serving component name in cycle racing history. The company built its name on supplying teams and has every year since. Existing teams supplied by Campagnolo will already have a good deal of material and spares, but in a team’s first year the supply is a bit larger to compensate for the lack of anything left over from previous years. At the end of each racing season, many riders will have to keep their old bikes going until the new ones arrive in January. That means racking up thousands of kilometers on them in all kinds of weather.

Having said that, the team bikes will get brand-new components for the first build every year, and, with electronic shifting becoming the accepted choice now for most riders, all the big teams are looking for new components. Campagnolo will supply 90 pairs of its electronic EPS Ergopower shifters and 132 front and rear EPS derailleurs; then for stopping there are 90 pairs of brakes and 140 sets of bottom bracket cups. The most popular cassette choice seems to be 11–25, and the team will get 140 of them for a season as the workhorse cassette ratio suitable for most terrain; however, 11–27 and 11–29 are becoming more popular, as are the 52/36 compact drive cranks — essential it seems these days for riding up the Angrilu. Crank length varies from 170 to 180 with the most popular being 172.5mm and 175mm. Campagnolo supplies 60 pairs of each crank length.

“To develop bicycle componentry requires not only patience and skills but experiences — not only good experiences but bad ones, too.”—VALENTINO CAMPAGNOLO ON PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

And it’s not responsible solely for equipping the road bikes. Added to the list are 42 sets of time trial levers and EPS command interfaces — essential for a team’s TT bikes. Wheel-wise: 150 pairs of wheels with discs, with aero wheels and climber’s specialist wheels making up a part of that. The teams will also use 29 pairs of standard hubs for hand building.

And what about tires? I asked Kris Withington how many tubulars Garmin goes through in a season.

“We received around one thousand tubulars from Vittoria at the start of the year, including the special pavé tires for the classics,” he said. “In the Tour, we go through around 60 to 70 standard racing tires. It’s enough to keep 50 or 60 pairs of wheels shod and ready for use. When they puncture, you always change the tubular. The guys will take that to the hotel and do it while the race is going on, so it can be ready for use the next day. We prepare all our spare tubulars at the service course in the days before a race. We use the tubulars until they’re really worn — okay, so it’ll go on the spare bike on the car, and one day it’ll go on the spare wheel, and then it’s pretty worn out, but there are always a few more days left in it.

“But this year, for example, David Millar, Ryder Hesjedal, and Tyler Farrar — those three will every day have more or less new tires. The domestiques will get the worn material, and they will use that material pretty much until they puncture. The best riders always get the new material — the best material — and the rest what’s left. Because, at the end of the year, when we run three racing programs, you’d run out of tubulars — especially if you’re just pulling them off every day — so you have to be resourceful, too.”

“It was in 1972, we were exhibiting components at the Milan bike show, and at the time Shimano was nothing at all to European people, but our booth was next to the De Rosa booth. And every day I of course attended the show, and I became friends with signor De Rosa — Ugo — and one day I asked him to make a bicycle for me. He checked my body size and everything, and several months later he sent me a complete bicycle — but [starts laughing] together with Campagnolo components! So you know I immediately changed to Dura-Ace. . . .”—YOZO SHIMANO ON SHIMANO ENTERING THE WORLD OF PROFESSIONAL BIKE RACING

Back at the service course, Omega Pharma–Quick-Step’s Specialized bikes are equipped with SRAM’s RED components. Although they may be relatively new to the road scene, they are fairly typical of a component supplier. So we asked SRAM what its average World Tour team goes through every year.

“Product is divided throughout team service course, several race trucks, and the riders’ home-training material. There are usually 30 riders per team with around four to five bikes each, so all major teams run at least 150 bikes, and we supply our current three World Tour teams in 2013 with SRAM RED groupsets (Omega Pharma–Quick-Step Pro Cycling, Saxo-Tinkoff Team, and Cannondale Pro Cycling Team) and two of these (Saxo-Tinkoff and OPQS) we supply with Zipp Wheels and handlebar and stem products, too.”

Last, but by no means least, there are the spares. Over a season, a team will use nearly 300 chains and over 450 pairs of brake pads. They will run through several bearing sets and new tools specific to the latest developments, so each mechanic’s tool and spares kit will be updated accordingly. Most teams will also use a lot of water bottles, around 25,000 in one year. Then there are the contact points: around 250 pairs of pedals and 400 saddles. It adds up to a lot of equipment, and it happens every year.

Adapted with permission of VeloPress from Bike Mechanic: Tales from the Road and the Workshop by Guy Andrews and Rohan Dubash with photography by Taz Darling. Preview the book at velopress.com/wrench.