A version of this article appeared in the May issue of BRAIN.

By Alan Cote

Could a “Check Engine” light be coming to bikes? Shimano is thinking that way, and has filed a patent application for using artificial intelligence processing paired with sensors to monitor wear and maintenance of bicycle components.

US Patent Application 20200010138, published on Jan. 9, gives a glimpse of a system for bicycles analogous to the on-board-diagnostic systems that automobiles have used for decades.

As is often the case, the application is not exactly a spec sheet for a new product line. Rather, it broadly claims the use of a digital processor to generate information related to deterioration, wear, and failure of various bicycle components, in some cases using sensors embedded in those components. And to boot, it uses AI processing to continue learning, based on actual wear rates.

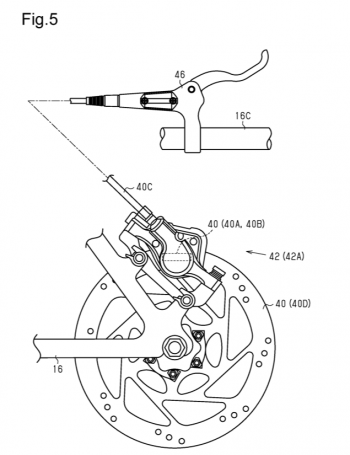

Components listed that can be monitored include: brakes (calipers, pads, shoes, hoses, cables rotors); drivetrain (sprockets, chains, crankarms, bottom bracket, crankshaft, pedals); wheels (hubs, spokes, rims, tires), lights, seatposts, handlebar grips, suspension components, batteries, various e-bike components, and more.

Different versions of the system are described, which vary in complexity. One version infers component wear using some combination of sensors that measure vehicle speed and crank rotation. Other factors like temperature can be added in. More sophisticated examples use sensors built into components to feed information to the processor. One example described is disc brake calipers with instrumentation to detect the initial position and the contact position of the pads relative to the rotor.

The AI — or machine learning, for a less ominous term — ncludes a “learning mode,” where the system takes note of the actual interval when a component gets replaced, to improve its knowledge of actual wear. For example, via GPS the system can determine a bike’s deceleration rate, and use that for rough estimates of brake wear. Add-in brake caliper sensors and there are better data to work with. Either way, a few cycles of brake pad replacement would further inform the system about expected wear. Ditto for shocks, drivetrain parts, etc.

The AI — or machine learning, for a less ominous term — ncludes a “learning mode,” where the system takes note of the actual interval when a component gets replaced, to improve its knowledge of actual wear. For example, via GPS the system can determine a bike’s deceleration rate, and use that for rough estimates of brake wear. Add-in brake caliper sensors and there are better data to work with. Either way, a few cycles of brake pad replacement would further inform the system about expected wear. Ditto for shocks, drivetrain parts, etc.

What might this technology mean for the industry? It seems most applicable to rental and share bikes, where large numbers of bikes must be maintained by a single company or owner. It’s also potentially a tool for managing liability and risk with such bikes. For retail shops, it might mean mechanics needing to learn new computer-based diagnostic skills, much like automobile mechanics who have laptops on their workbenches.

It also furthers the approach taken pioneered by Shimano – but also in the playbook of SRAM, Campagnolo, and others – of making components that are not cross-compatible with those from competitors. Here, exclusivity could extend beyond the usual proprietary drivetrains and brakes to additional components, from dropper posts to tires.

When this could come to fruition is anyone’s guess – keeping in mind that Shimano applies for patents on many inventions and technologies that never becoming products in the market.

Alan Cote is a Registered Patent Agent & principal of Green Mountain Innovations LLC. He’s a past contributing writer to Bicycling, Outside, and other magazines, and a former elite-level racer. He also serves as an expert witness in bicycle-related legal cases.