Editor's note: A version of this article ran in the January issue of Bicycle Retailer & Industry News. If you don't receive our magazine (in print or digital format), please sign up for a free subscription at bicycleretailer.secure.darwin.cx/Z2COTRLB.

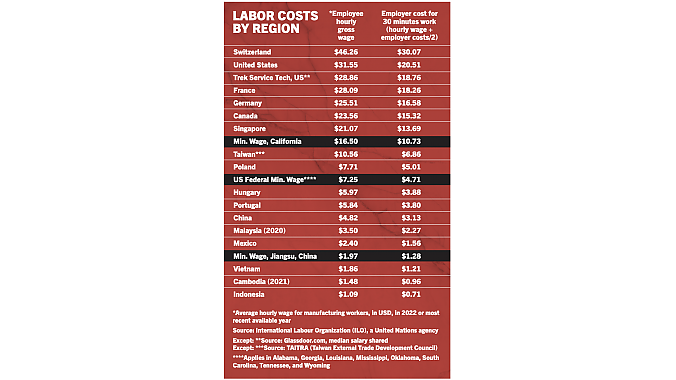

BOULDER, Colo. (BRAIN) — In an article in December, we quoted Pedego founder Don DiCostanzo saying that Pedego couldn't build bikes in the U.S. because of the stark difference in labor costs between California and China. He said it would cost $30 an hour for labor in California while Chinese factories pay $1 an hour.

The comment led to some discussion online. Turn out, DiCostanzo was exaggerating only a bit, as the chart at the bottom of this page shows. The minimum hourly wage in the Jiangsu region of China, where there are many bike factories, is $1.97, but the factories might pay considerably more than the minimum.

And while California is one of the most expensive labor markets in the U.S., why not build in South Carolina or Georgia?

The difference between labor costs in Asia and the U.S., while stark, are actually manageable, industry sources tell BRAIN. It turns out that other factors weigh heavier when brands decide where to make or assemble their bikes.

As long as most derailleurs, tires, suspension and other parts remain made in Asia, most bikes will be made there, too.

Unfortunately for fans of domestic manufacturing, Asia currently holds the lead in most of those factors, as well.

THE MATH ON BIKE ASSEMBLY

Many point to bike assembly as a stepping stone to bringing manufacturing back to the U.S. Assembly is a quick enough process that the difference is labor costs can be overcome.

For example, Giant says it can assemble a bike in 30 minutes in its Taiwan factories. Clearly more complicated bikes take longer, but the right column in the chart to the left shows varying labor costs by country and region for a 30-minute assembly. Find the back of an envelope to do the math if you wish: multiply the 30-minute cost by 2 or 3 for an assembly of a more complicated bike by a less efficient factory.

For example, Giant says it can assemble a bike in 30 minutes in its Taiwan factories. Clearly more complicated bikes take longer, but the right column in the chart to the left shows varying labor costs by country and region for a 30-minute assembly. Find the back of an envelope to do the math if you wish: multiply the 30-minute cost by 2 or 3 for an assembly of a more complicated bike by a less efficient factory.

If a U.S. assembler could match Giant's speed, the difference in labor cost would work out to $10-$20 per bike assembly. That's significant, but it's on a scale where a favorable tariff, or some savings in shipping costs, could more than make up the difference. For example, the current tariff (in January 2025) on a complete bike from China is 36%, which can amount to hundreds of dollars. On a mass market juvenile bike, the tariff on a Chinese bike valued at $70 at port is $25 — probably more than the extra labor cost for assembly, if the U.S.-assembled bike was subject to no tariffs. In other words, the savings in tariffs would nearly offset the extra labor costs.

So why aren't more bikes being made in the U.S., or at least assembled here? There must be other reasons than labor costs.

In interviews with sources at a variety of companies around the industry, we learned that when it comes to deciding where to make bikes, labor costs and tariffs are factors, along with factory efficiency and quality. But proximity to component manufacturers is often the most important determinant. As long as most derailleurs, tires, suspension and other parts remain made in Asia, most bikes will be made there, too.

Having parts makers near a bike assembly facility, especially a large one, has major benefits for the brands that assemble there.

It's somewhat counter-intuitive: Proponents of U.S. manufacturing and assembly tout the advantages of being "close to market," so brands are better able to respond to market demands, ups and downs. And that can be true, especially for boutique brands that offer custom builds. But for most, assembling bikes in the U.S. means ordering parts, often on 90-day lead times, from an Asian factory. The parts then need to be flown or shipped across the ocean. Canceling or changing an order takes months, and the brand's money is tied up the whole time in the orders, not to mention the assembly or manufacturing facility overhead. So in that case domestic assembly reduces flexibility and adds to lead times.

Assembling in Asia, especially in Taiwan for mid- and upper-priced bikes, is more flexible. "If you have a big enough (component) order, the lead times are shorter. If there's a defect, you can send it back and get a replacement really quick. It reduces the administrative headaches," said the owner of one small bike brand that assembles bikes in Taiwan, mostly using Taiwanese components and frames.

Asian factories are almost always more automated and efficient than a U.S. assembly line for a small or medium brand. And through-put is more important than hourly labor costs, many told BRAIN.

Industry consultant Jay Townley was in charge of moving Schwinn's bike and fitness production out of Chicago to lower-cost regions of the U.S. and then Taiwan and China in the 1980s. He said on trips to far-flung factories, accompanied by a team of Schwinn's expert purchasers, product managers and manufacturing engineers, he soon learned that factory efficiency and automation trump hourly labor costs every time. At the time, China's labor was significantly cheaper than Taiwan's, but Taiwan's bike factories, especially Giant's, were much more automated and efficient, he said. "It really dawned on me that the difference between the hourly wages in Taiwan and China makes no difference if the automation is there. If the cycle time is faster, you can afford to pay twice the labor to get it done in half the time," he said.

In deciding where to move production, Townley and his team considered a wide array of factors, including shipping costs, tariff rates, product quality and factory efficiency. Hourly wages were pretty far down the list, he recalls.

"The move to Cambodia and Vietnam is not driven by labor as much as getting the hell out of China."

"The magic is in the processes: how the assembly line is laid out, how automation is brought to bear and how well can the factory get a quality product in the carton with the least amount of application of labor," he said.

In recent years, the industry has shifted more bike assembly and manufacturing from China to even lower labor cost nations including Vietnam and Cambodia. But Townley and other industry experts interviewed for this article said labor costs are not why the industry is going there.

"The move to Cambodia and Vietnam is not driven by labor as much as getting the hell out of China," because of concerns about tariffs imposed by the U.S. and Europe, he said.

Labor costs are not always a red herring. Manufacturing some products, such as carbon fiber frames and components, remains very labor-intensive. Giant says its top-of-the-line carbon road frame requires 20 hours of labor. Less exotic frames take less time, but the labor costs are why China and other low-cost nations dominate the carbon fiber frame and component markets. Even some of the most boutique bike brands, some of which assemble bikes in the U.S. or Europe, still get their carbon frames made in China, Vietnam, Cambodia, or other Southeast Asian countries.

Of course a few small-volume manufacturers make carbon frames and parts like rims in the U.S. and Europe. They rely on high prices, low volumes, tighter margins, increased automation and customization options to compete. The sustainable, scalable solution is the automation of carbon manufacturing — or a new technology that is more easily manufactured. Some have claimed they found the solution, but the current lack of U.S. or European-made carbon products in the middle, high-volume part of the market tells the story.

Denver-based brand Guerrilla Gravity claimed to have a carbon manufacturing process that was highly automated and its parent company, Revved, tried to sell the process to other industries before collapsing last year. Interestingly, Taiwan’s Astro Tech Co., Limited, paid $1.22 million for GG's carbon fiber frame manufacturing equipment when Revved’s assets were liquidated. Astro Tech has supplied U.S. brands including Niner, Huffy and Cycles Devinci in the past. Astro Tech also hired two former Revved employees temporarily to assist in setting up the equipment in Taiwan. The equipment was partially damaged in shipment, according to court records.

SCALE IS A KEY

So even without changes in labor costs, could the industry, perhaps with some government help, change the other factors working against U.S. assembly and manufacturing? Yes, but it would be very difficult.

China makes about 143 million bikes, e-bikes, and scooters a year while the U.S. buys 10-12 million bikes a year. If you made bike parts, where would you put your plant?

Asia's industry has the scale to merit huge, efficient, automated factories and the nearby component makers that make them even more efficient. The industry employs millions of people, and thus the governments pay attention to supporting them. No U.S. supplier or government act can change that difference in scale.

WHAT CAN TARIFFS DO?

U.S. assemblers are most frustrated when tariffs appear to be working against them. Kent International Chairman Arnold Kamler is a regular in the financial media, explaining that tariffs on components and raw materials discourage U.S. assembly, especially when complete products made of the same stuff earn exclusions from the tariffs, as complete bikes did for several years under the Trump and Biden administrations. Kamler says a favorable tariff situation, plus savings in shipping, can make U.S. assembly financially viable for Kent even with the difference in labor costs.

Kent assembles several hundred thousand bikes a year in South Carolina with Chinese frames and parts (the rest of the several million bikes Kent sells annually are made in China or Malaysia). If Chinese components and raw materials were excluded from tariffs for assemblers, Kamler said he would invest in more manufacturing and assembly in the U.S., including manufacturing aluminum frames and parts here.

It's not just bike makers, either. Light & Motion assembled its bike and dive lights in California for years, mostly using Chinese components. For a time, those components were subject to tariffs while complete bike lights were excluded from tariffs (an exclusion probably earned on safety grounds; bike helmets were excluded as well). While the exclusion for lights ended last year, for years Light & Motion had to compete with complete lights brought in from China without tariffs, while it paid tariffs on its light components. The company closed late last year.

"Building products in the U.S. was always a lofty ideal,” Light & Motion CEO Daniel Emerson told BRAIN in an email following the closure. “Cheaper is better so to China they go …” Emerson said, referring to light buyers.