As a follow-up to last year’s three-part series on the e-bike landscape (available here, here and here, respectively), I reached out to e-bike guru Ed Benjamin of eCycleElectric for an update. Among other services, Benjamin's company tracks e-bike imports to the USA for clients in the bicycle, e-bike, automobile, motorcycle, and e-bike equipment industries. These imports enter the country under more than a dozen HS numbers (Department of Commerce import codes), which calls for a lot of data-crunching and interpretation.

It's amazing how much has changed in just one year.

For one thing, while imports of pedal-only bikes essentially tanked in 2019 over market pressures and fear of restrictive tariffs, e-bikes were booming. But because e-bikes are not counted in the bicycle import data, that boom went largely unnoticed by industry observers.

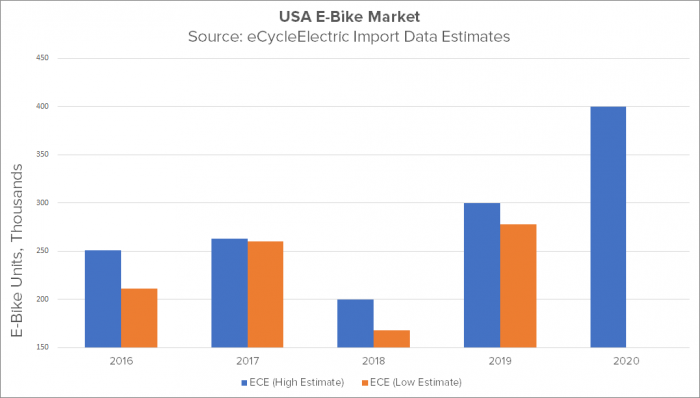

Last year, Benjamin estimated 2019 e-bike imports would grow to 300,000 pieces. This year, his adjusted numbers for 2019 come to 287,000. "The benefits of e-bikes simply outweighed the tariff concerns," he concludes. For 2020, factory closures and reopening issues over the coronavirus make it impossible to say with accuracy, but he forecasts shipments could reach 400,000 pieces.

Consumer choice is rewriting the e-bike landscape

The single biggest piece of news, Benjamin says, is that "By 2019, the largest share of imports had shifted away from a handful of companies who sold primarily through Amazon under various brands. Instead, the bulk is now going to consumer-direct e-bike specialists, brick and mortar e-bike specialists (EBDs), and conventional bicycle brands in the IBD channel."

“Americans have shown us in the last year that they understand and are willing to pay for the value in a better e-bike.”

Rather than looking at distribution channels, Benjamin says, it may be more useful to classify e-bikes by price point. For sure, there are still bargain-bin models being sold on Amazon, but these are a fraction of what they were just a few years ago. "Americans have shown us in the last year" Benjamin explains, "that they understand and are willing to pay for the value in a better ebike."

This is a huge shift and one that's driving the expansion of other channels. "So we see the $1,500 to $3,000 price point is really taking off. The major bicycle brands with IBD distribution are becoming more and more powerful, both because they have better (and therefore more expensive) products and by virtue of their distribution and service networks."

That's good news for traditional bike shops, but they're still just the tip of the e-bike iceberg.

Breaking it down even further, Benjamin agrees the market falls into three basic price-driven categories. "The bottom price niche is consumer-direct sales through Amazon, for well under $1,000," he says. "But these bikes are usually unsatisfying."

Moving up from there is the price point of approximately $1,500 to $2,500. Above $2,500, and stretching all the way up to $10,000 or more, is where the majority of IBD brands play...but not all, as we shall see.

Five market-leading e-bike brands

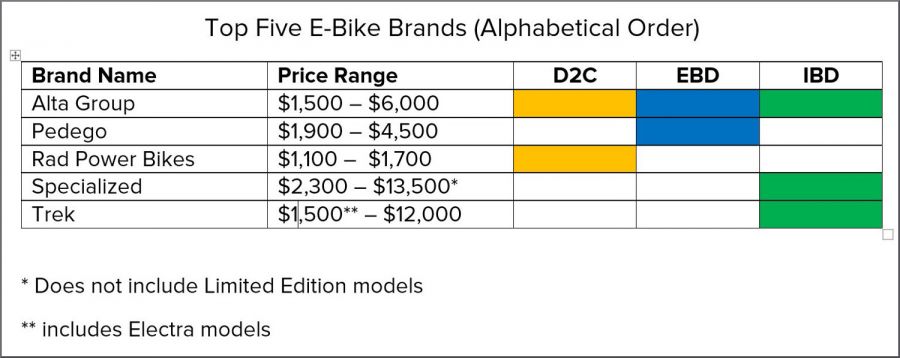

According to Benjamin, the five leading e-bike brands (in no particular order) are Rad Power, Pedego, Trek, Specialized, and the Alta Group — Raleigh, IZIP, et al. These five collectively enjoy about 70% of the total e-bike market in 2020. (The reason for including all Alta brands as one is simply because that's the way the import documents are labeled; no further breakdown is possible.)

Trek and Specialized, of course, are well known to BRAIN readers and fiercely competitive, with respect both to each other and other players in the market. But I wanted to know more about the other brands, especially their target audiences and sales strategies.

"We're used to growing by 30-40% per year and suddenly it's triple digits," said Pedego's founder, Don DiCostanzo. "Fortunately we have good control of our supply chain. Ninety percent of our bikes are from Vietnam, and the supply is steady, so we have inventory. Nobody can keep 3–4X inventory in stock, but we try to keep up.

"Our customer is radically different than the IBD customer. It's people who don't think of themselves as cyclists. They think Schwinn is the biggest brand in the U.S., and they've never heard of Trek, Specialized, or Giant. Our customer is that other 85-90%, and that's the broader, bigger market."

We have five successful brands with a collectively dominant market share covering a myriad of price points, target audiences and distribution strategies. This suggests less a group of direct competitors than a “brand ecology” of differentiated yet effective strategies.

Alta's chief commercial officer, Larry Pizzi, has a broader view of the market, which is fitting, because his brands sell in all three sales channels — D2C, EBD, and IBD. (A bit of background: out of the acquisition from Accell Group N.V., Alta now owns Diamondback, IZIP and Redline, and has a distribution agreement with Accell on the Raleigh, Haibike and Ghost brands for the U.S.) "We have e-bikes in every one of those brands except Diamondback today," Pizzi says, "and we sell significant numbers in e-bikes across all of them.

"A lot of things have changed in the last nine months or so, and IZIP has a lot of attention. At higher price points — above $2,000, say — most of the volume happens in brick and mortar, whether that's an IBD or EBD. EBDs in the U.S. are selling about the same unit volume as our IBD network.

"The biggest group of consumers has been aging baby boomers," Pizzi continues, "but it's gotten a lot broader as younger consumers look for transportation alternatives. The biggest demographic is 45–65, and it tends to lean male. There's a lot of female participation in women buying long-tail cargo bikes, too. That's turned into a significant segment, people who are using e-bikes to replace car trips. It's also great to see many hardcore cyclists looking at the faster Class-3 e-bikes and e-MTBs and thinking they are pretty cool."

Despite repeated calls and emails over a period of weeks, a spokesperson for Rad Power Bikes was unavailable as of press time. But Ed Benjamin sums up the company's approach this way:

"Rad Power is the master of consumer-direct internet advertising," Benjamin says. "Their customer base is younger and more comfortable making large-ticket purchases direct. D2C is a great model for them. The Amazon customer is buying to see if they like the category; the EBD (although it's becoming more of an electric bike emphasis) is selling into the broader community, and the IBD is selling to its traditional customer base."

What's most interesting here is that we have five successful brands with a collectively dominant market share covering a myriad of price points, target audiences, and distribution strategies. This suggests less a group of direct competitors than a "brand ecology" of differentiated yet effective strategies, each suited to different audiences, channels, and price ranges.

If so, this e-bike "Quintumvirate" may end up being a more stable arrangement than the zero-sum, dog-eat-dog battle that currently characterizes the pedal-only market.

This brand ecology notion could work equally well in the pedal-only sphere, too. Perhaps one way out of our current battle among more or less identical brands and strategies would be for competitors to differentiate themselves by developing products suited to a broader range of cycling consumers and riding styles. And, along with a growing market for e-bikes and the current "bike boomlet," that could be a very healthy thing for brands, for retailers, and for the industry as a whole.

Rick Vosper has been helping companies in the bicycle business solve marketing problems since 1989. Email rick@rvms.com for a free consultation.