Even as smart and well thought-through as it clearly is, the true significance of Shimano’s new gearbox patent in the e-bike era is its potential to redefine how disruptive new technologies can succeed in the bicycle business. And that has huge implications for the health and long-term direction of the industry itself.

Shifting the shifting paradigm

The bike boom of the 1970’s was created and defined by a disruptive product technology: the drop-bar racing-style bicycle, and more importantly, by its derailleur drivetrain. Some number of chainrings up front, some number of cogs on a freewheel in the rear, and the whole system enabled by one or more increasingly sophisticated derailleurs to move the chain around.

Functionally, the whole point of the derailleur drivetrain was to allow a cyclist to go faster and farther over more varied terrain with less effort. Almost as an afterthought, it also created the enthusiast-driven market paradigm that has defined the bicycle — not to mention the bicycle business — to the present day. The larger question of whether a particular cyclist even cared about faster/farther/easier didn’t merit serious consideration.

Bicycles were defined by a simple equation: their efficiency in turning human effort into forward motion. The quality (and generally, price) of a bike was defined by how efficiently it solved that equation. And the definitive aspect of that solution was easily packaged and sold as weight savings. Everything else — frame and component stiffness, aerodynamics, “ride quality” (whatever that means), was secondary, at least in sales terms.

Mountain bikes were just derailleur drivetrains adopted to go off roads and to more extreme conditions. Suspension only existed to help them get there. Exotic materials, aerodynamics, frame geometry, new wheel and tire and pedal designs, none of that stuff altered the fundamental equation or the paradigm behind it.

To be sure, weight gain could be tolerated by the market if the offsetting performance benefits were high enough: think BMX or mountain bike durability, or weight-adding yet successful innovations like brake-lever mounted indexed and/or electronic shifting, aero frames and components, suspension systems and dropper posts. All were evaluated against their increase in weight.

At the end of the day, weight ruled supreme, less by virtue of its actual value in solving the efficiency equation than for the fact that it was so darned easy to quantify. Even UCI limitations on minimum bike weight didn’t stop the consumer market. Across comparable designs, the lighter bike was (almost) always betterm … and always pricier.

Weight ruled supreme, less by virtue of its actual value in solving the efficiency equation than for the fact that it was so darned easy to quantify.

The other side of the equation — power input —could be tweaked through elements like bike fit, positioning, and rider fitness to squeeze out a few more watts. But on the sales floor, that was effectively a fixed variable. At least until the addition of a secondary motor, first in the form of the moped and more recently and successfully, as the modern e-bike. Even today, weight is still a primal factor driving e-bike price and in evaluating e-bike quality.

What the industry has critically failed to notice is how fundamentally the advent of e-bikes has altered the efficiency equation and therefore, disrupted the faster/farther/easier paradigm. Until Shimano’s new gearbox design, that is. And there are plenty of other potential disruptors available, both now and in the pipeline.

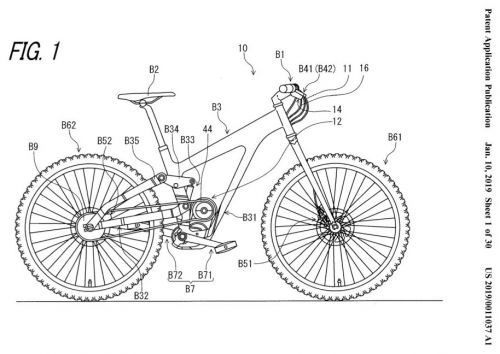

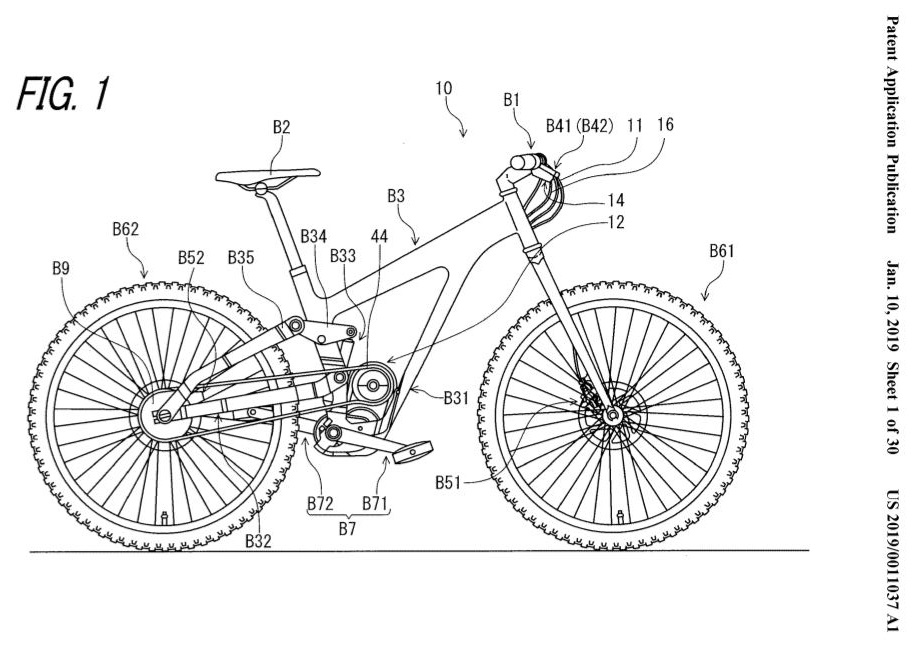

About that gearbox: it’s not about the gearbox

The ultimate value of a gearbox drive — whether from Shimano, Pinion, Intra Drive or others — lies in how it can integrate with the e-bike format to create a seismic change in how we think about bicycle performance. It’s heavier, it’s marginally less mechanically efficient, but with a secondary power source available, these are now secondary considerations in how we evaluate bicycle performance.

There are literal decades of passed-over innovations already conceptualized or developed which can benefit cyclists and, most important for industry purposes, bring more buyers into our stagnating market.

In addition to gearboxes, consider formerly weight- or efficiency-prohibitive ideas like shaft or all-wheel drives, infinitely variable transmissions, run-flat tires, or integrated component systems. All were rejected by developers and/or the market, largely on the basis of weight. But with the acceptance of the e-bike, all are back on the table now. Even better, once validated with e-bikes, these and many other ideas can cross back over to pedal-only formats.

Realistically, there is no reason the weight/power-efficiency paradigm should apply to anything other than (some categories of) racing bikes. Why shouldn’t cargo bikes use IVTs, beach cruisers run shaft drives, downhill sleds incorporate antilock braking systems, or commuter bikes take advantage of run-flat technology? There are literal decades of passed-over innovations already conceptualized or developed that can benefit cyclists and, most important for industry purposes, bring more buyers into our stagnating market.

The functional limitation is not the technologies themselves, or their provable benefits, but the market — and the industry’s — willingness to accept them. Leaving e-bikes aside for a minute, look at how slow the industry was to take up mountain bikes and AheadSets, let alone all the kvetching and moaning going on to this day about wheel sizes, disc brakes, and component interchangeability with 50-year-old standards.

It comes down to what design legend Raymond Loewy called MAYA theory: Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable. If you’re not familiar with the name, Loewy is known as “the father of industrial design” and creator of everything from the iconic Coca-Cola bottle shape to the layout of Skylab’s crew living quarters. So when Loewy talked about the limitations of net novelty in design, designers listened, and still do.

Apple is famous for implementing MAYA in its development strategy, for instance. Notable disasters that failed to respect MAYA principles include the Ford Edsel, Crystal Pepsi, Google Glass and possibly the coolest bicycle of all time, the Bowden Spacelander.

As Loewy put it back in 1957, "The adult public's taste is not necessarily ready to accept the logical solutions to their requirements if the solution implies too vast a departure from what they have been conditioned into accepting as the norm."

Fortunately for the industry, public acceptance of the e-bike has already increased what we might call its acceptable net novelty quotient. Now it’s up to us to take advantage of that newfound appetite for paradigm-busting innovation by delivering products to satisfy it.

Defining the post-paradigm product spectrum

So what will the post-efficiency-at-all-costs paradigm look like, product-wise? I propose it will work on a continuum, based on how important rider efficiency is to the success of the product. This can be expressed in two ways: how fast or far we want the bike to be ridden, and how much of the bike’s input energy has to come from the rider.

The adoption curve becomes obvious: the less it’s intended to perform like a track or racing bike, the more it can look like —and incorporate functional elements from — an electric motorcycle, and vice-versa.

At the left side of the continuum is the track racing bike: 100% rider-powered and stripped of everything that doesn’t help make it more efficient, including derailleurs and brakes. Proceeding to the other pole, we encounter bikes where maximizing energy efficiency is increasingly less relevant to its purpose and/or as the importance of rider energy input trends toward zero. We move through various casual and recreational pedal-only categories to beach cruisers, low riders, then through increasingly powerful species of e-bikes, all the way over to the far right side of the continuum, the electric motorcycle.

Once we move our paradigm from rider efficiency what I’m going to call “rider efficiency relevance,” the adoption curve becomes obvious: the less it’s intended to perform like a track or racing bike, the more it can look like —and incorporate functional elements from — an electric motorcycle. and vice-versa.

Starting with, but not limited to, gearboxes.

Contrarywise, the more the target user identifies as a cyclist at their time of purchase, the more they will want an e-bike that looks like a traditional pedal-only bicycle. In terms of design, it is notable that while specialty retail bike companies try to visually integrate their e-bikes’ power supply, electronics and motor into traditional frame designs, the industry has yet to come out with a production “mechanical doping” model which is indistinguishable from one of their pedal-only road or mountain bikes. (The number of racer wannabees intent on poaching Strava KOMs alone could drive profits in this niche for years.)

The same continuum also maps to the existing e-bike classes. Class 1 (pedal-assist/pedelec) bikes will end up looking most like traditional designs and therefore be the slowest to adopt gearboxes and/or other technologies. Class Two (throttle) bikes will be more open to change by virtue of the lower rider energy input required. And Class 3 (speed pedelecs) will ultimately be the most accepting category for the same reason.

There may even be an effect similar to the Uncanny Valley in facial recognition: is that a bicycle or a motorcycle? Are those really pedals, or merely the functional equivalent of crank-mounted foot pegs? The answer, by the way, is the same as it is for every other design and technical innovation. It’s subject to the principles of MAYA design and basic functionality, but in the end, the market always wins. Always.

So that’s the blueprint. New technology plus e-bikes equals a way to shift the dominant paradigm. Best of all, key technologies and the map for implementing that shift are already on the table, starting with a new generation of workable gearbox drives.